No, the guy himself never visited, but his spirit is at the excellent Bibliothèque national (BnF) exhibition ‘Imprimer! L’Europe de Gutenberg’ at their F. Mitterrand site (below right).

Of course, both of the Gutenberg bibles that the BnF owns are displayed (title picture). To emphasise the status of Gutenberg, a 1831 painting depicts him as a latter-day saint Jerome inventing movable type in his study (below left). As often, Gutenberg’s invention responded to a acutely felt need for a quicker and cheaper way to produce books. However, books continued to be expensive and libraries needed to chain them to the desks to avoid stealing (below right).

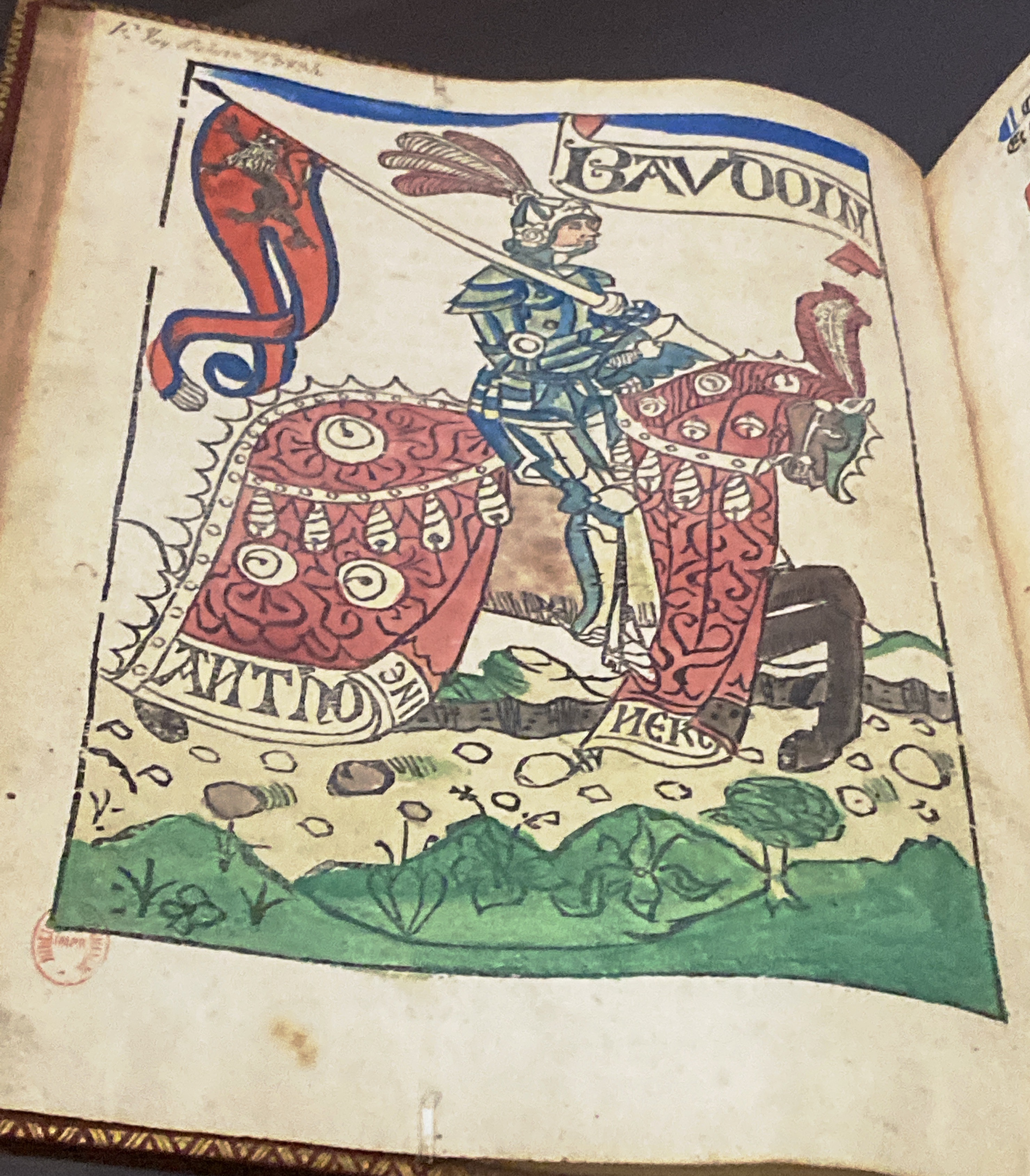

Although woodblock printing and even movable type had been in use in the Far East for hundreds of years, in the West the introduction of movable type to a limited character set exploded the industry and brought new readers to books as the prices tumbled. The first printed books were religious, classical or court texts, as these had an established readership. The first printing of Dante’s ‘Divina Commedia’ came out in 1471 (below left) and Baudoin’s stories about the ‘Comte de Flandre’ in 1485, with a hand-coloured woodblock illustration (below right).

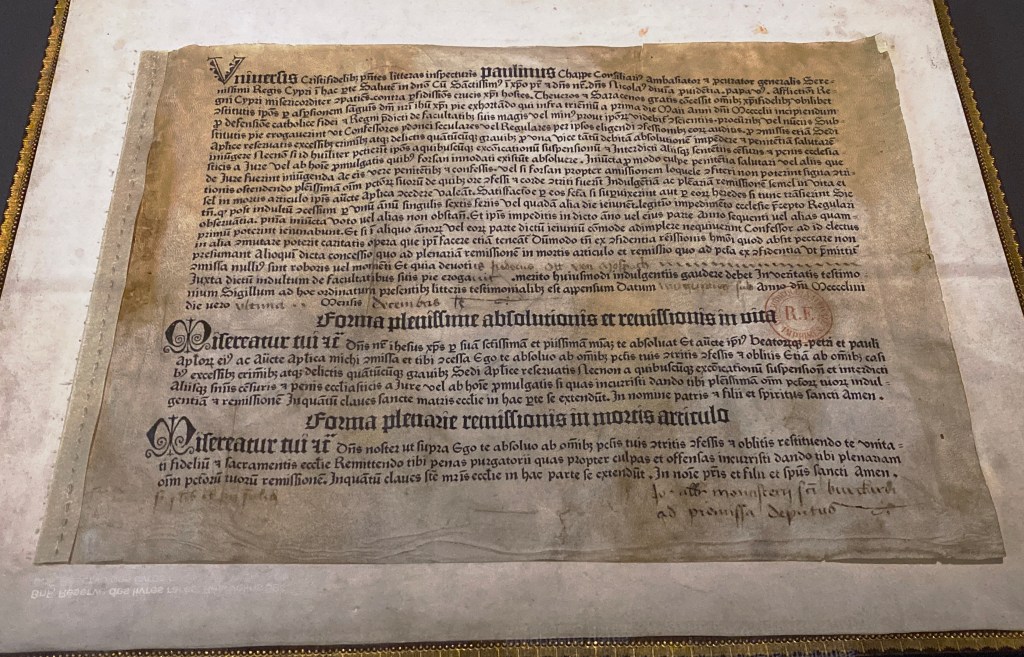

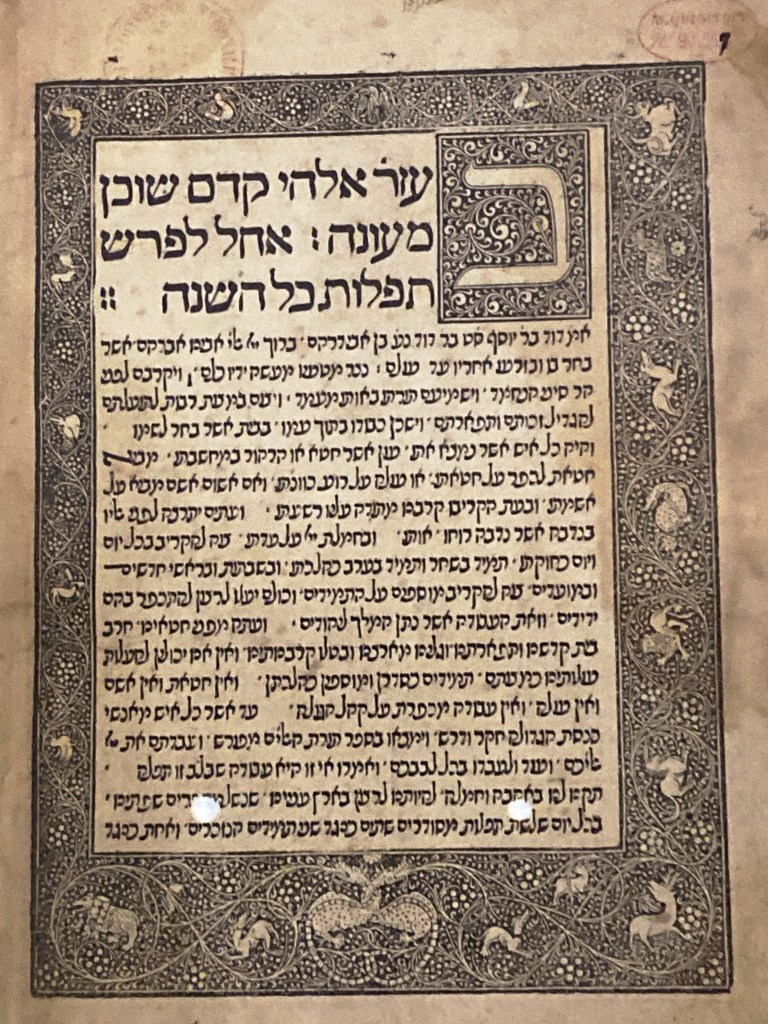

The catholic church saw an opportunity to increase revenue by multiplying its production of indulgencies and immediately in 1454 ordered forms (from Gutenberg himself) for the purpose (below left). Besides Latin, printers started producing books in other languages and character sets very soon. Below right is a Hebrew commentary on the prayer book, printed in Lisbon in 1489.

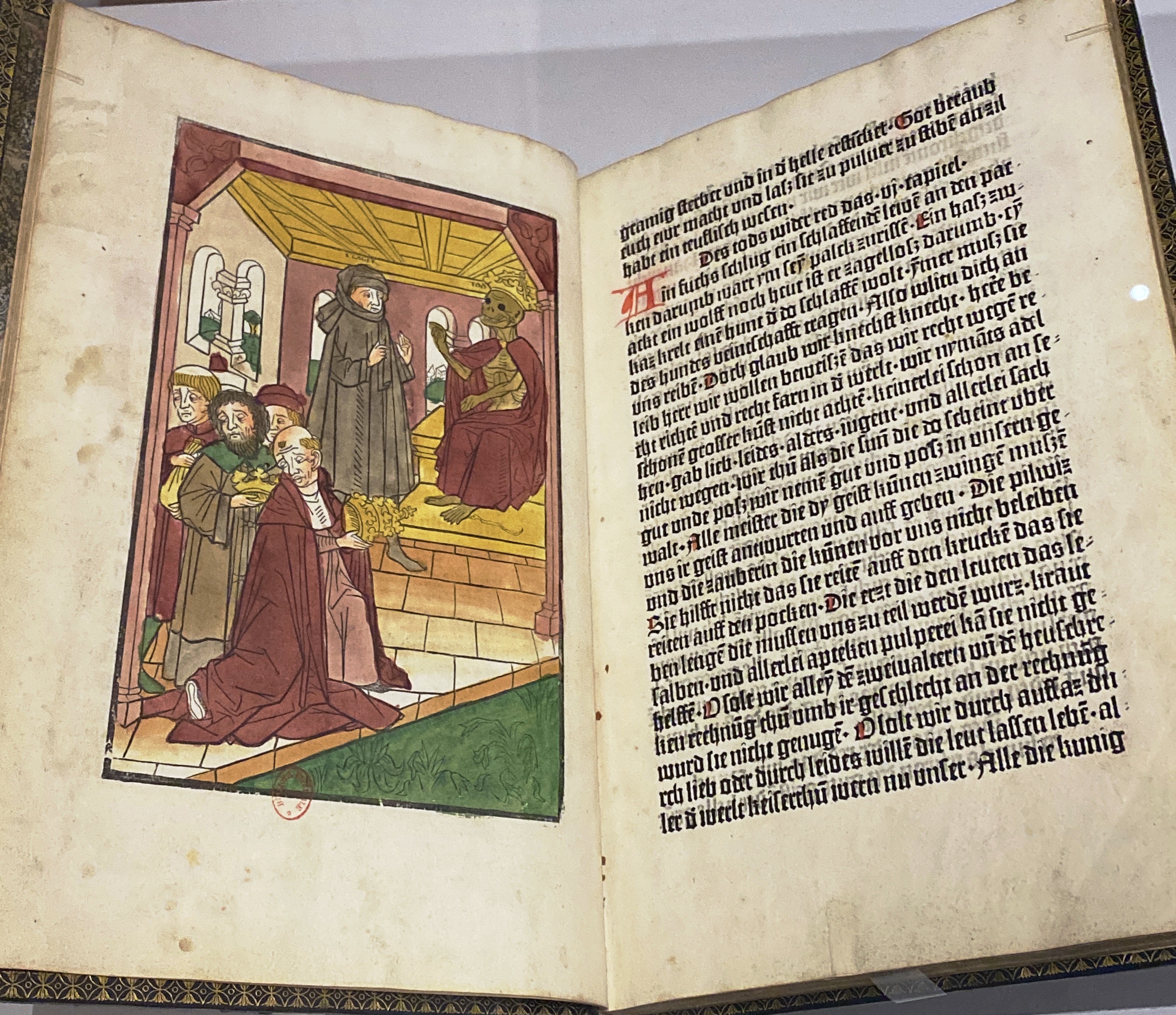

Popular stories were not far behind as the printers got hang of the trade and produced smaller and cheaper books – although occasionally still with hand-coloured illustrations. Below left is a German moral story ‘Ackermann von Böhmen’. But colour gave way to black and white woodblock images as thse were easier and cheaper to include (below right an illustrated version of ‘Divina Commedia’).

And schoolbooks, of course – below left is Euclid’s ‘Geometry’ printed in 1482 (in Latin, naturally). More immediately useful mght have been the ‘Rechnung auf alle Kauffmanschafft’, printed in German in 1489, and specifically targeted to apprentice merchants.

We still argue about copyright – and so they did in the second half of the 15th century. The illustrations of Albrcht Dürer were so popular that the books where they were printed needed a warning that they should not be copied – below are the famous riders of the apocalypse from 1498.

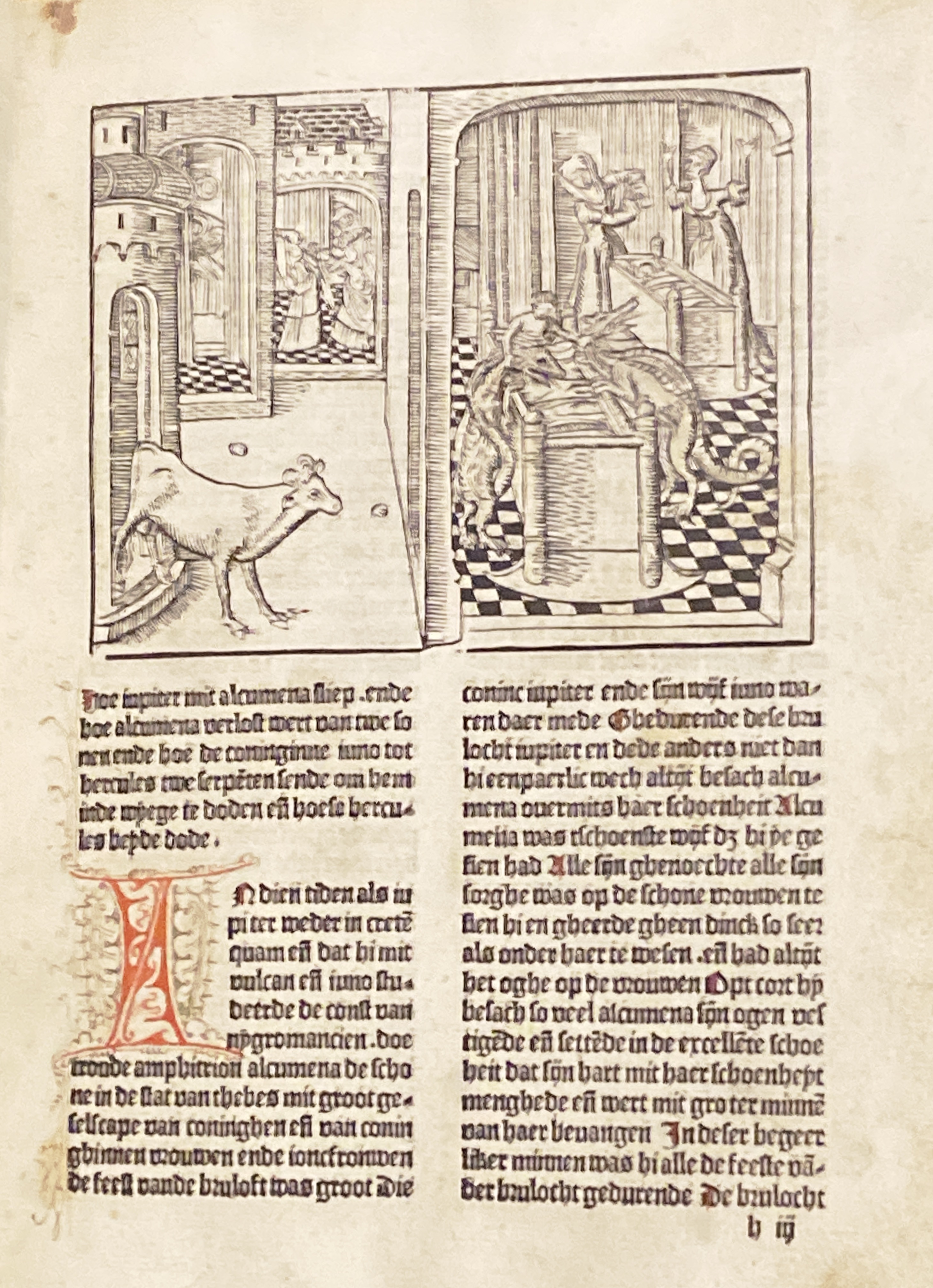

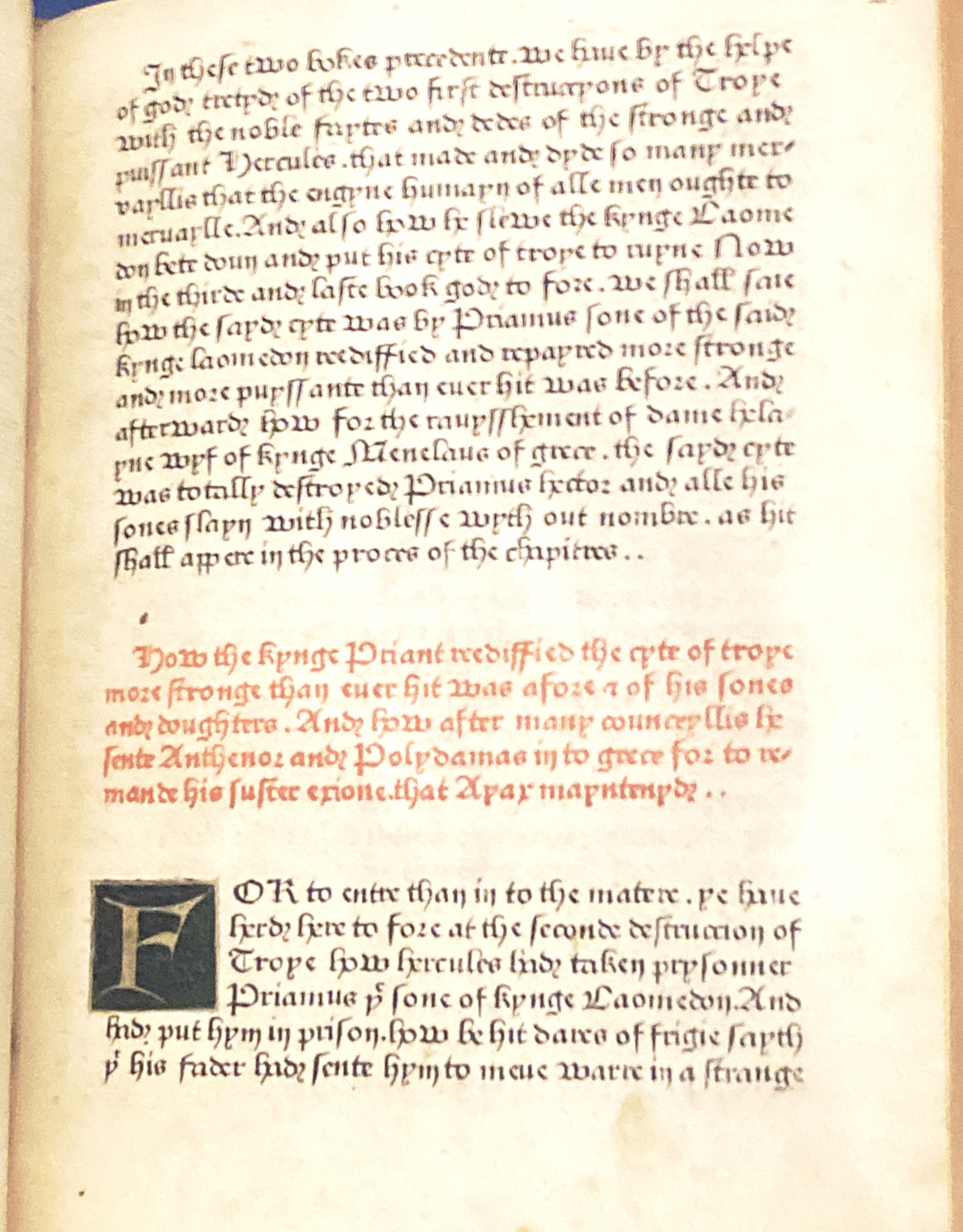

It took some time for illustrated manuscripts to disappear, as they were prestige items for the rich and powerful. Thus, below is a manuscript in French produced for the court of the count of Hainaut, and printed Flemish and English texts of Raoul Lefèvre’s Troyan stories, all from 1485-95.

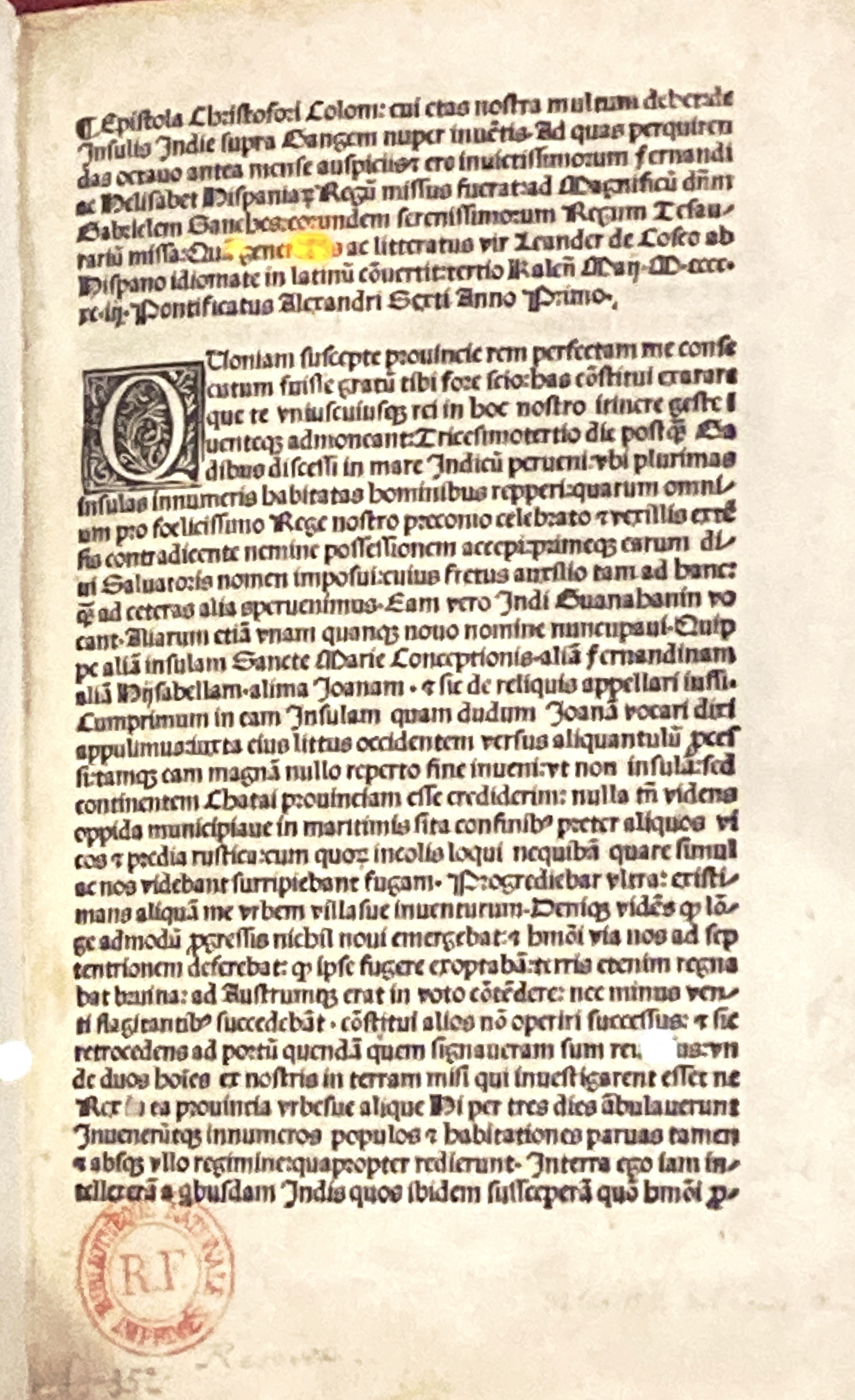

A certain Christopher Columbus had edited his travel diary for his employers, but fame arrived when these were published in Latin at least in six editions around Europe in 1493-94 (below left). Below right is an illustration of a popular topic at the time ‘the debate between wine and water’ – ostensibly about the benefits of drinking one or the other.

Gradually printing turned the book trade upside down, as there were more books supplied than any reader could consume. But it allowed the quick spreading of ideas, led to new levels of available information that needed to be managed, and meant that the world moved on more rapidly than before.