Built for war, famous for a peace treaty – that has been the fate of the sleepy garrison town of Hamina in South-Eastern Finland.

In the 18th century, the conquests of the previous century that made Sweden a dominant power in Northern Europe, were gradually lost. In 1721 after the Great Northern War, the border with Russia was moved to approximately where the border between Finland and Russia is now. This led to Sweden losing its historical fortress in Viipuri (Vyborg), and a replacement border fortification was needed to guard against any new threats from Russia. Thus in 1723 a new fortified city called Fredrikshamn (shortened to Hamina in Finnish) was established, bearing the name of the king of Sweden, Fredrik I. It replaced an earlier town located in the same place that was destroyed in the war.

The town was built symmetrically to form an octogon, with six defensive bastions surrounding it. However, its time as a Swedish fortress was short, as already in 1743, after the Russo-Swedish war, the border moved again and Hamina became a fortified Russian garrison town.

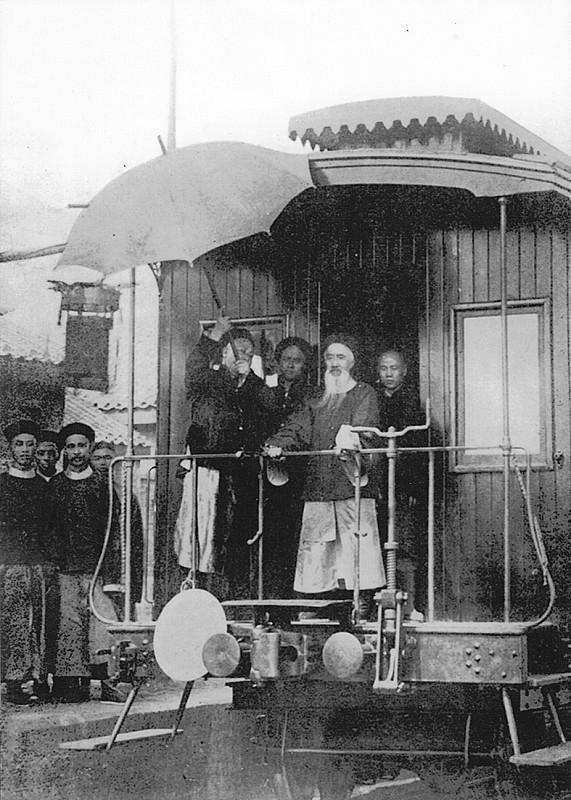

A bit later, the war of 1808-1809 meant that Sweden lost the whole of Finland, and the border moved to where it is now between Finland and Sweden. This was no foregone conclusion, though, as Russian troops had in fact occupied Umeå in the Western part of the realm (current Sweden), almost 400 km further south. Thus the peace negotiations were difficult for the Swedes – the Russians had invited them to Hamina for this purpose. The resulting Treaty of Hamina that was signed in the town hall (pictured) was in fact the last peace treaty between Sweden and Russia, as the Swedes had by this time had enough of military adventures.

In fact, the military fame of the town continued even after the peace of 1809. Under the new autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland, the town got to host an officer training school for the Russian army. Many of the students who initially served in the imperial Russian army, became important figures in the Finnish army after the Russian revolution, including Field Marshal Mannerheim who commanded the Finnish troops against the Russians in 1939-1944. This military connection of Hamina has in no way ended, as after Finnish independence, the same facilities have been used by the reserve officer training school.

By the way, the fact that the border between Finland and Russia is now again in the same place as in 1721 is no coincidence – Stalin specifically demanded the border of Peter the Great after the wars with Finland, both in 1940 and 1944.

Sources: ‘The Treaty of Hamina 1809’, Wikipedia